“Solar Powerhouse” China Is Leading Asia’s Green Energy Movement

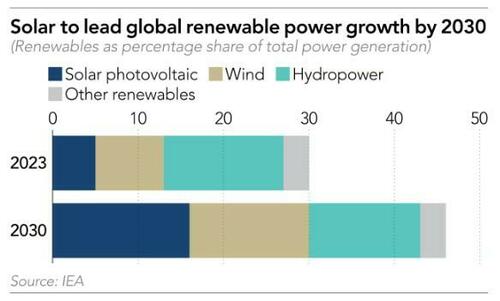

“Solar Powerhouse” China Is Leading Asia’s Green Energy Movement If you’re trying to implement green energy solutions in Asia, chances are you’re going to need to rely on China one way or another. Southeast Asia’s demand for renewable energy is rising, driven by tech manufacturing and data center growth, according to Nikkei. Solarvest, the region’s leading renewable energy provider, plans to capitalize on this boom by increasing imports from China, according to a local manager. That manager told Nikkei: “We aim to invest more in the next couple of years. Buying equipment and components from Chinese suppliers, who have mastered the supply chain and solar tech, gives us the best opportunity to generate green energy with a price that is low enough to compete against fossil fuels.” Through its Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has extended its influence over power infrastructure in countries like Malaysia, Thailand, and Pakistan. However, the U.S. has criticized China for subsidizing manufacturers and underpricing goods, leading to tariffs and trade barriers. The Nikkei report says that despite U.S. opposition, China maintains an edge with economies of scale and growing climate urgency. Solar energy, seen as the most accessible renewable source, attracted $500 billion in investment in 2024, surpassing all other energy types, according to the International Energy Agency. Offshore wind projects take over eight years to complete, while solar plants can be built in under two, making solar a faster choice for companies transitioning to renewables, industry leaders told Nikkei. This urgency is especially pronounced in emerging Asian economies like Malaysia and Thailand, which rely on fossil fuels but aim to attract tech giants like Apple and Google, committed to 100% renewable energy through the RE100 initiative. China dominates the global solar energy market, housing leading players like Longi Green Energy, Tongwei, and Jinko Solar, as well as